ARTICLE OF IRAQ

IRAQ,a country located in WEST ASIA, largely coincides with the ancient region of MESOPOTAMIA,often referred to as the cradle

of civilization.

HISTORY OF IRAQ. The history of MESOPOTAMIA extend back to the lower paleolithic period,with significant developments continuing through the establishment of the Caliphate in the late 7th century AD,after which the region became known as IRAQ.within its border lies the ancient land of sumer,which emerged between 6000 and 5000 BC DURING the NEOLITHIC UBAID PERIOD

1)OFFICIAL NAME; Republic of Iraq.

2) POPULATION;40,194,216.

3)OFFICIAL LANGUAGES; Arabic,Kurdish.45) MONEY; New Iraq Dinar.

GEOGRAPY OF IRAQ,

HISTORY OF IRAQ IRAQ is dominated by two famous River;the Tigris and the Euphrates. They flow southeast from the highlands in the plains towards the Persian

Gulf,the fertile region between these rivers has had many names throughout history,including AL-JAZIRA, or ‘the Island,’in ARABIC and MESOPOTAMIA in GREEK,

Iraq

Iraq is dominated by two famous rivers: the Tigris and the Euphrates.

FAST FACTS

- OFFICIAL NAME: Republic of Iraq

- FORM OF GOVERNMENT: Parliamentary democracy

- CAPITAL: Baghdad

- POPULATION: 40,194,216

- OFFICIAL LANGUAGES: Arabic, Kurdish

- MONEY: New Iraq dinar

- AREA: 168,754 square miles (437,072 square kilometers)

- MAJOR RIVERS: Tigris, Euphrates

GEOGRAPHY

Iraq is dominated by two famous rivers: the Tigris and the Euphrates. They flow southeast from the highlands in the north across the plains toward the Persian Gulf. The fertile region between these rivers has had many names throughout history, including Al-Jazirah, or “the island,” in Arabic and Mesopotamia in Greek.

Many parts of Iraq are harsh places to live. Rocky deserts cover about 40 percent of the land. Another 30 percent is mountainous with bitterly cold winters. Much of the south is marshy and damp. Most Iraqis live along the fertile plains of the Tigris and Euphrates.

Map created by National Geographic Maps

PEOPLE AND CULTURE

Iraq is one of the most culturally diverse nations in the Middle East. Arabs, Kurds, Turkmen, Assyrians, Mandaeans, and Armenians, among others, speak their own languages and retain their cultural and religious identities.

Iraqis once had some of the best schools and colleges in the Arab world. That changed after the Gulf War in 1991 and the United Nations sanctions that followed. Today only about 40 percent of Iraqis can read or write.

NATURE

Safeguarding Iraq’s wildlife is a big job. There are essentially no protected natural areas in the country. And with an ongoing war, the government is, understandably, more concerned with protecting people and property than plants and animals.

Before the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, several species were considered at risk, including cheetahs, wild goats, and dugongs. Scientists have not been able to assess the condition of these animals since the war started.

Iraq’s rivers and marshes are home to many fish, including carp that can grow up to 300 pounds (135 kilograms) and sharks that swim up from the Persian Gulf.

GOVERNMENT AND ECONOMY

In January 2005, Iraqis voted in the country’s first democratic elections in more than 50 years. It took another three months for a government to take office, but Iraq’s new democracy was set up to ensure all ethnic groups are represented.

Iraq has the world’s second largest supply of oil. But international sanctions during the 1990s and the instability caused by the 2003 war have left Iraq in poverty.

Left: IRAQI FLAG

Right: IRAQ DINAR

Photograph by L Hill, Dreamstime

HISTORY

Iraq’s history is full of unsettling changes. In the past 15 years alone, it has witnessed two major wars, international sanctions, occupation by a foreign government, revolts, and terrorism. But Iraq is a land where several ancient cultures left stamps of greatness on the country, the region, and the world.

Iraq is nicknamed the “cradle of civilization.” Thousands of years ago, on the plains that make up about a third of Iraq, powerful empires rose and fell while people in Europe and the Americas were still hunting and gathering and living more primitive lives.

The Sumerians had the first civilization in Iraq around 3000 B.C. The first type of writing, called cuneiform, came out of Uruk, a Sumerian city-state. Around 2000 B.C., the Babylonians came into power in southern Mesopotamia. Their king, Hammurabi, established the first known system of laws.

Babylonian rule ended in 539 B.C. when the Persians took over. In A.D. 646, Arabs overthrew the Persians and introduced Islam to Iraq. Baghdad was soon established as the leading city of the Islamic world. In 1534, the Ottomans from Turkey conquered Iraq and ruled until the British took over almost 400 years later.

Iraq became an independent country in 1932, although the British still had a big influence. In 1979, Saddam Hussein and his Baath Party took control of Iraq and promoted the idea that it should be ruled by Arabs. Hussein ruled as a ruthless dictator. In 1980, he started a long war with Iran, and in 1991, he invaded Kuwait, triggering the first Gulf War.

In 2003, after years of sanctions against Iraq, the United States invaded again out of concern that Saddam Hussein was making dangerous weapons. U.S. military forces quickly reached Baghdad and threw the Baathists from power. Saddam Hussein was captured, tried for crimes against humanity, and executed.

Map created by National Geographic Maps

A man descends a structure called a ziggurat in Ur, Iraq

HISTORY OF IRAQ.

IRAQ is oneof the most culturally diverse nations in the Middle East,Arabs, Kurds,Turkmen, Assyrians,Mandaeans,among others,speak their own languages

and retain their cultural and religious identities.

IRAQIS once had some of the best schools and colleges in the Arab World. That changed after the Gulf War in 1991 and the United Nations sanctions that followed.

Today only about 40 percent of Iraqis can read or write,

HISTORY OF IRAQ.Safegyarding IRAQ ‘S Wildlife is a big job.There are essentially no protected natural areas in the country .And with an ongoing War ,the government is,understandably,more concerned with protecting people and property than plants and animals..

IRAQ’S river and marshes are home to many fish,including carp that can grow up to 300 pounds(135 Kilograms)and sharks that swin up from the Persian Gulf.

HISTORY OF IRAQ.The Flag of Iraq has three equal horizontal stripes of red ,white,and black,with Arabic phrase ‘Allahu Akbar'(GOD is Great)in green kufic script centered on the

W hite stripe.The flag,s width-to- lenght ratio is 2 to 3.

it differs from previous versions in that it uses dark green for the takbir and removes three green stars that were persent in the 1963 version.

HISTORY OF IRAQ.1921 ,

The flag of Faysal,son of Husayn ibn ALI,with horizontal stripes of black-white-green and a red triangle at the hoist.

HISTORY OF IRAQ.1959 ,

A flag with vretical stripes of black-white-green,and a central embelem with a yellow sun framed by eight red rays.

HERE FAMOUS LOCATION OF IRAQ,

HISTORY OF IRAQ.ERBIL CITADEL ,

A histroric site with a bazaar,tea houses,and restaurants.

HISTORY OF IRAQ.IMAM ALI HOLY SHRINE

A historic site that some say is a spiritual experience,S

THE HOLY SHRINE OF IMAM HUSSAIN,

A religious site in Karbala that some say provides for your needs

- Kabab, which is grilled meat on a stick.

- Dolma ,stuffed spiced rice wrapped in grape leave.

HISTORY OF IRAQ.

IRAQ ‘S HISTORY; AN INTERACTIVE TIMELINE

IRAQ held a national legislative election of 325 representative in 2010,the elected council of representatives apporoved a new government,in DECEMBE

2012 AD,

MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT IN IRAQ’

| office | name |

| Higher Education and Scientific Reaserch Minister \ | Naim Abd Yassir al-Aboudi |

| Industry and Minerals Minister | Khalid Najim |

| Environment Minister | Nizar Moahmmed Saeed Amidi |

| Labour & Social Affair Minister | Ahemed Jassem Saber Al-Asadi |

MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE IN IRAQ

The ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources is responsible for developping government policy on food security and supply.

Geography & TravelCountries of the World

Table of Contents

Iraq

PrintCiteShareFeedback

Also known as: ʿIraq, Al-ʿIrāq, Al-Jumhūrīyyah al-ʿIrāqīyyah, Republic of Iraq

Written by

Richard L. Chambers,

Gerald Henry Blake•All

Fact-checked by

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

Last Updated: Oct 19, 2024 • Article HistoryAsk the Chatbot a Question

News •

Iraq moves to revoke Saudi broadcaster’s license after report angered militia supporters • Oct. 19, 2024, 3:34 PM ET (AP) …(Show more)

Iraq, country of southwestern Asia.

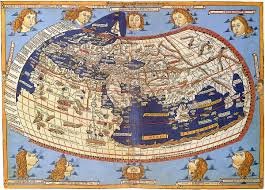

During ancient times, lands that now constitute Iraq were known as Mesopotamia (“Land Between the Rivers”), a region whose extensive alluvial plains gave rise to some of the world’s earliest civilizations, including those of Sumer, Akkad, Babylon, and Assyria. This wealthy region, comprising much of what is called the Fertile Crescent, later became a valuable part of larger imperial polities, including sundry Persian, Greek, and Roman dynasties, and after the 7th century it became a central and integral part of the Islamic world. Iraq’s capital, Baghdad, became the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate in the 8th century. The modern nation-state of Iraq was created following World War I (1914–18) from the Ottoman provinces of Baghdad, Basra, and Mosul and derives its name from the Arabic term used in the premodern period to describe a region that roughly corresponded to Mesopotamia (ʿIrāq ʿArabī, “Arabian Iraq”) and modern northwestern Iran (ʿIrāq ʿAjamī, “foreign [i.e., Persian] Iraq”).

See article: flag of Iraq

Audio File: National anthem of Iraq

See all mediaHead Of Government: Prime Minister: Mohammed Shia al-SudaniCapital: BaghdadPopulation: (2024 est.) 44,528,0002Head Of State: President: Abdul Latif RashidForm Of Government: multiparty republic with one legislative house (Council of Representatives of Iraq [3291])

Iraq gained formal independence in 1932 but remained subject to British imperial influence during the next quarter century of turbulent monarchical rule. Political instability on an even greater scale followed the overthrow of the monarchy in 1958, but the installation of an Arab nationalist and socialist regime—the Baʿath Party—in a bloodless coup 10 years later brought new stability. With proven oil reserves second in the world only to those of Saudi Arabia, the regime was able to finance ambitious projects and development plans throughout the 1970s and to build one of the largest and best-equipped armed forces in the Arab world. The party’s leadership, however, was quickly assumed by Saddam Hussein, a flamboyant and ruthless autocrat who led the country into disastrous military adventures—the Iran-Iraq War (1980–88) and the Persian Gulf War (1990–91). These conflicts left the country isolated from the international community and financially and socially drained, but—through unprecedented coercion directed at major sections of the population, particularly the country’s disfranchised Kurdish minority and the Shiʿi majority—Saddam himself was able to maintain a firm hold on power into the 21st century. He and his regime were toppled in 2003 during the Iraq War.

Land

Iraq is one of the easternmost countries of the Arab world, located at about the same latitude as the southern United States. It is bordered to the north by Turkey, to the east by Iran, to the west by Syria and Jordan, and to the south by Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Iraq has 36 miles (58 km) of coastline along the northern end of the Persian Gulf, giving it a tiny sliver of territorial sea. Followed by Jordan, it is thus the Middle Eastern state with the least access to the sea and offshore sovereignty.

Relief

Iraq’s topography can be divided into four physiographic regions: the alluvial plains of the central and southeastern parts of the country; Al-Jazīrah (Arabic: “the Island”), an upland region in the north between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers; deserts in the west and south; and the highlands in the northeast. Each of these regions extends into neighbouring countries, although the alluvial plains lie largely within Iraq.Britannica QuizThe Country Quiz

Alluvial plains

The plains of lower Mesopotamia extend southward some 375 miles (600 km) from Balad on the Tigris and Al-Ramādī on the Euphrates to the Persian Gulf. They cover more than 51,000 square miles (132,000 square km), almost one-third of the country’s area, and are characterized by low elevation, below 300 feet (100 metres), and poor natural drainage. Large areas are subject to widespread seasonal flooding, and there are extensive marshlands, some of which dry up in the summer to become salty wastelands. Near Al-Qurnah, where the Tigris and Euphrates converge to form the Shaṭṭ al-ʿArab, there are still some inhabited marshes. The alluvial plains contain extensive lakes. The swampy Lake Al-Ḥammār (Hawr al-Ḥammār) extends 70 miles (110 km) from Basra (Al-Baṣrah) to Sūq al-Shuyūkh; its width varies from 8 to 15 miles (13 to 25 km).

Al-Jazīrah

North of the alluvial plains, between the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers, is the arid Al-Jazīrah plateau. Its most prominent hill range is the Sinjār Mountains, whose highest peak reaches an elevation of 4,448 feet (1,356 metres). The main watercourse is the Wadi Al-Tharthār, which runs southward for 130 miles (210 km) from the Sinjār Mountains to the Tharthār (Salt) Depression. Milḥat Ashqar is the largest of several salt flats (or sabkhahs) in the region.

Get Unlimited Access

Try Britannica Premium for free and discover more.

Deserts

Western and southern Iraq is a vast desert region covering some 64,900 square miles (168,000 square km), almost two-fifths of the country. The western desert, an extension of the Syrian Desert, rises to elevations above 1,600 feet (490 metres). The southern desert is known as Al-Ḥajarah in the western part and as Al-Dibdibah in the east. Al-Ḥajarah has a complex topography of rocky desert, wadis, ridges, and depressions. Al-Dibdibah is a more sandy region with a covering of scrub vegetation. Elevation in the southern desert averages between 300 and 1,200 feet (100 to 400 metres). A height of 3,119 feet (951 metres) is reached at Mount ʿUnayzah (ʿUnāzah) at the intersection of the borders of Jordan, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia. The deep Wadi Al-Bāṭin runs 45 miles (75 km) in a northeast-southwest direction through Al-Dibdibah. It has been recognized since 1913 as the boundary between western Kuwait and Iraq.

The northeast of Iraq

The mountains, hills, and plains of northeastern Iraq occupy some 35,500 square miles (92,000 square km), about one-fifth of the country. Of this area only about one-fourth is mountainous; the remainder is a complex transition zone between mountain and lowland. The ancient kingdom of Assyria was located in this area. North and northeast of the Assyrian plains and foothills is Kurdistan, a mountainous region that extends into Turkey and Iran.

The relief of northeastern Iraq rises from the Tigris toward the Turkish and Iranian borders in a series of rolling plateaus, river basins, and hills until the high mountain ridges of Iraqi Kurdistan, associated with the Taurus and Zagros mountains, are reached. These mountains are aligned northwest to southeast and are separated by river basins where human settlement is possible. The mountain summits have an average elevation of about 8,000 feet (2,400 metres), rising to 10,000–11,000 feet (3,000–3,300 metres) in places. There, along the Iran-Iraq border, is the country’s highest point, Ghundah Zhur, which reaches 11,834 feet (3,607 metres). The region is heavily dissected by numerous tributaries of the Tigris, notably the Great and Little Zab rivers and the Diyālā and ʿUẓaym (Adhaim) rivers. These streams weave tortuously south and southwest, cutting through ridges in a number of gorges, notably the Rū Kuchūk gorge, northeast of Barzān, and the Bēkma gorge, west of Rawāndūz town. The highest mountain ridges contain the only forestland in Iraq.

Drainage

The Tigris-Euphrates river system

Iraq is drained by the Tigris-Euphrates river system, although less than half of the Tigris-Euphrates basin lies in the country. Both rivers rise in the Armenian highlands of Turkey, where they are fed by melting winter snow. The Tigris flows 881 miles (1,417 km) and the Euphrates 753 miles (1,212 km) through Iraq before they join near Al-Qurnah to form the Shaṭṭ al-ʿArab, which flows another 68 miles (109 km) into the Persian Gulf. The Tigris, all of whose tributaries are on its left (east) bank, runs close to the high Zagros Mountains, from which it receives a number of important tributaries, notably the Great Zab, the Little Zab, and the Diyālā. As a result, the Tigris can be subject to devastating floods, as evidenced by the many old channels left when the river carved out a new course. The period of maximum flow of the Tigris is from March to May, when more than two-fifths of the annual total discharge may be received. The Euphrates, whose flow is roughly 50 percent greater than that of the Tigris, receives no large tributaries in Iraq.

Irrigation and canals

Many dams are needed on the rivers and their tributaries to control flooding and permit irrigation. Iraq has giant irrigation projects at Bēkma, Bādūsh, and Al-Fatḥah. In the late 1970s and early ’80s, Iraq completed a large-scale project that connected the Tigris and Euphrates. A canal emerges from the Tigris near Sāmarrāʾ and continues southwest to Lake Al-Tharthār, and another extends from the lake to the Euphrates near Al-Ḥabbāniyyah. This connection is crucial because in years of drought—aggravated by more recent upstream use of Euphrates water by Turkey and Syria—the river level is extremely low. In 1990 Syria and Iraq reached an agreement to share the water on the basis of 58 percent to Iraq and 42 percent to Syria of the total that enters Syria. Turkey, for its part, unilaterally promised to secure an annual minimum flow at its border with Syria. There is no tripartite agreement.

Following the Persian Gulf War, the Iraqi government dedicated considerable resources to digging two large canals in the south of the country, with the apparent goal of improving irrigation and agricultural drainage. There is evidence, however, that these channels were also used to drain large parts of Iraq’s southern marshlands, from which rebel forces had carried out attacks against government forces. The first was reportedly designed to irrigate some 580 square miles (1,500 square km) of desert. The vast operation to create it produced a canal roughly 70 miles (115 km) long between Dhī Qār and Al-Baṣrah governorates. The second, an even grander scheme, was reportedly designed to irrigate an area some 10 times larger than the first. This canal, completed in 1992, extends from Al-Yūsufiyyah, 25 miles (40 km) south of Baghdad, to Basra, a total of some 350 miles (565 km).

The two projects eventually drained some nine-tenths of Iraq’s southern marshes, once the largest wetlands system in the Middle East. Much of the drained area rapidly turned to arid salt flats. Following the start of the Iraq War in 2003, some parts of those projects were dismantled, but experts estimated that rehabilitation of the marshes would be impossible without extensive efforts and the expenditure of great resources.

Soils

The desert regions have poorly developed soils of coarse texture containing many stones and unweathered rock fragments. Plant growth is limited because of aridity, and the humus content is low. In northwestern Iraq, soils vary considerably: some regions with steep slopes are badly eroded, while the river valleys and basins contain some light fertile soils. In northwest Al-Jazīrah, there is an area of potentially fertile soils similar to those found in much of the Fertile Crescent. Lowland Iraq is covered by heavy alluvial soils, with some organic content and a high proportion of clays, suitable for cultivation and for use as a building material.

Salinity, caused in part by over-irrigation, is a serious problem that affects about two-thirds of the land; as a result, large areas of agricultural land have had to be abandoned. A high water table and poor drainage, coupled with high rates of evaporation, cause alkaline salts to accumulate at or near the surface in sufficient quantities to limit agricultural productivity. Reversing the effect is a difficult and lengthy process.

Heavy soil erosion in parts of Iraq, some of it induced by overgrazing and deforestation, leaves soils exposed to markedly seasonal rainfall. The Tigris-Euphrates river system has thus created a large alluvial deposit at its mouth, so that the Persian Gulf coast is much farther south than in Babylonian times.

Climate of Iraq

Iraq has two climatic provinces: the hot, arid lowlands, including the alluvial plains and the deserts; and the damper northeast, where the higher elevation produces cooler temperatures. In the northeast cultivation fed by precipitation is possible, but elsewhere irrigation is essential.

In the lowlands there are two seasons, summer and winter, with short transitional periods between them. Summer, which lasts from May to October, is characterized by clear skies, extremely high temperatures, and low relative humidity; no precipitation occurs from June through September. In Baghdad, July and August mean daily temperatures are about 95 °F (35 °C), and summer temperatures of 123 °F (51 °C) have been recorded. The diurnal temperatures range in summer is considerable.

In winter the paths of westerly atmospheric depressions crossing the Middle East shift southward, bringing rain to southern Iraq. Annual totals vary considerably from year to year, but mean annual precipitation in the lowlands ranges from about 4 to 7 inches (100 to 180 mm); nearly all of this occurs between November and April.

Winter in the lowlands lasts from December to February. Temperatures are generally mild, although extremes of hot and cold, including frosts, can occur. Winter temperatures in Baghdad range from about 35 to 60 °F (2 to 15 °C).

In the northeast the summer is shorter than in the lowlands, lasting from June to September, and the winter considerably longer. The summer is generally dry and hot, but average temperatures are some 5–10 °F (3–6 °C) cooler than those of lowland Iraq. Winters can be cold because of the region’s high relief and the influence of northeasterly winds that bring continental air from Central Asia. In Mosul (Al-Mawṣil), January temperatures range between 24 and 63 °F (−4 and 17 °C); readings as low as 12 °F (−11 °C) have been recorded.Britannica QuizWhich Country Is Larger By Area? Quiz

In the foothills of the northeast, annual precipitation of 12 to 22 inches (300 to 560 mm), enough to sustain good seasonal pasture, is typical. Precipitation may exceed 40 inches (1,000 mm) in the mountains, much of which falls as snow. As in the lowlands, little rain falls during the summer.

A steady northerly and northwesterly summer wind, the shamāl, affects all of Iraq. It brings extremely dry air, so hardly any clouds form, and the land surface is thus heated intensively by the sun. Another wind, the sharqī (Arabic: “easterly”), blows from the south and southeast during early summer and early winter; it is often accompanied by dust storms. Dust storms occur throughout Iraq during most of the year and may rise to great height in the atmosphere. They are particularly frequent in summer, with five or six striking central Iraq in July, the peak of the season.

Plant and animal life

Vegetation in Iraq reflects the dominant influence of drought. Some Mediterranean and alpine plant species thrive in the mountains of Kurdistan, but the open oak forests that formerly were found there have largely disappeared. Hawthorns, junipers, terebinths, and wild pears grow on the lower mountain slopes. A steppe region of open, treeless vegetation is located in the area extending north and northeast from the Ḥamrīn Mountains up to the foothills and lower slopes of the mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan. A great variety of herbs and shrubs grow in that region. Most belong to the sage and daisy families: mugwort (Artemisis vulgaris), goosefoot, milkweed, thyme, and various rhizomic plants are examples. There also are many different grasses. Toward the riverine lowlands many other plants appear, including storksbill and plantain. Willows, tamarisks, poplars, licorice plants, and bulrushes grow along the banks of the lower Tigris and Euphrates rivers. The juice of the licorice plant is extracted for commercial purposes. Dozens of varieties of date palm flourish throughout southern Iraq, where the date palm dominates the landscape. The lakesides and marshlands support many varieties of reeds, sedges, pimpernels, vetches, and geraniums. By contrast, vegetation in the desert regions is sparse, with tamarisk, milfoil, and various plants of the genera Ziziphus and Salsola being characteristic.

Birds are easily the most conspicuous form of wildlife. There are many resident species, though the effect of large-scale drainage of the southern wetlands on migrants and seasonal visitors—which were once numerous—has not been fully determined. The lion, oryx, ostrich, and wild ass have become extinct in Iraq. Wolves, foxes, jackals, hyenas, wild pigs, and wildcats are found, as well as many small animals such as martens, badgers, otters, porcupines, and muskrats. The Arabian sand gazelle survives in certain remote desert locations. Rivers, streams, and lakes are well stocked with a variety of fish, notably carp, various species of Barbus, catfish, and loach. In common with other regions of the Middle East, Iraq is a breeding ground for the unwelcome desert locust.

People

Modern Iraq, created by combining three separate Ottoman provinces in the aftermath of World War I, is one of the most religiously and ethnically diverse societies in the Middle East. Although Iraq’s communities generally coexisted peacefully, fault lines between communities deepened in the 20th century as a succession of authoritarian regimes ruled by exploiting tribal, sectarian, and ethnic divisions.

Ethnic groups

The ancient Semitic peoples of Iraq, the Babylonians and Assyrians, and the non-Semitic Sumerians were long ago assimilated by successive waves of immigrants. The Arab conquests of the 7th century brought about the Arabization of central and southern Iraq. A mixed population of Kurds and Arabs inhabit a transition zone between those areas and Iraqi Kurdistan in the northeast. Roughly two-thirds of Iraq’s people are Arabs, about one-fourth are Kurds, and the remainder consists of small minority groups.

https://e.infogram.com/_/0vnOQgbgHPNrhfN92w8o?parent_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.britannica.com%2Fplace%2FIraq%2FThe-northeast&src=embed#async_embed

Arabs of Iraq

Iraq’s Arab population is divided between Sunni Muslims and the more numerous Shiʿi Muslims. These groups, however, are for the most part ethnically and linguistically homogenous, and—as is common throughout the region—both value family relations strongly. Many Arabs, in fact, identify more strongly with their family or tribe (an extended, patrilineal group) than with national or confessional affiliations, a significant factor contributing to ongoing difficulties in maintaining a strong central government. This challenge is amplified by the numerical size of many extended kin groups—tribal units may number thousands or tens of thousands of members—and the consequent political and economic clout they wield. Tribal affiliation among Arab groups has continued to play an important role in Iraqi politics, and even in areas where tribalism has eroded with time (such as major urban centres), family bonds have remained close. Several generations may live in a single household (although this is more common among rural families), and family-owned-and-operated businesses are the standard. Such households tend to be patriarchal, with the eldest male leading the family.

Kurds

Although estimates of their precise numbers vary, the Kurds are reckoned to be the fourth largest ethnic group in the Middle East, following Arabs, Turks, and Persians. There are important Kurdish minorities in Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and Syria, and Iraq’s Kurds are concentrated in the relatively inaccessible mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan, which is roughly contiguous with Kurdish regions in those other countries. Kurds constitute a separate and distinctive cultural group. They are mostly Sunni Muslims who speak one of two dialects of the Kurdish language, an Indo-European language closely related to Modern Persian. They have a strong tribal structure and distinctive costume, music, and dance.

The Kurdish people were thwarted in their ambitions for statehood after World War I, and the Iraqi Kurds have since resisted inclusion in the state of Iraq. At various times the Kurds have been in undisputed control of large tracts of territory. Attempts to reach a compromise with the Kurds in their demands for autonomy, however, have ended in failure, owing partly to government pressure and partly to the inability of Kurdish factional groups to maintain a united front against successive Iraqi governments. From 1961 to 1975, aided by military support from Iran, they were intermittently in open rebellion against the Iraqi government, as they were during the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s and again, supported largely by the United States, throughout the 1990s.

After its rise to power, the Baʿath regime of Saddam Hussein consistently tried to extend its control into Kurdish areas through threats, coercion, violence, and, at times, the forced internal transfer of large numbers of Kurds. Intermittent Kurdish rebellions in the last quarter of the 20th century killed tens of thousands of Kurds—both combatants and noncombatants—at the hands of government forces and on various occasions forced hundreds of thousands of Kurds to flee to neighbouring Iran and Turkey. Government attacks were violent and ruthless and included the use of chemical weapons against Kurdish civilians; such incidents took place at the village of Ḥalabjah and elsewhere in 1988.

Following a failed Kurdish uprising in the wake of the Persian Gulf War, the United States and other members of the coalition that it led against Iraq established a “safe haven” for the Kurds in an area north of latitude 36° N that was under the protection of the international community. Thereafter the Kurds were largely autonomous. Kurdish autonomy is upheld in the 2005 constitution, which designates Kurdistan as an autonomous federal region.

Other minorities

Small communities of Turks, Turkmen, and Assyrians survive in northern Iraq. The Lur, a group speaking an Iranian language, live near the Iranian border. In addition, a small number of Armenians are found predominantly in Baghdad and in pockets throughout the north.

Languages

More than three-fourths of the people speak Arabic, the official language, which has several major dialects; these are generally mutually intelligible, but significant variations do exist within the country, which makes spoken parlance between some groups (and with Arabic-speaking groups in adjacent countries) difficult. Modern Standard Arabic—the benchmark of literacy—is taught in schools, and most Arabs and many non-Arabs, even those who lack schooling, are able to understand it. Roughly one-fifth of the population speaks Kurdish, in one of its two main dialects. Kurdish is the official language in the Kurdish Autonomous Region in the north. A number of other languages are spoken by smaller ethnic groups, including Turkish, Turkmen, Azerbaijanian, and Syriac. Persian, once commonly spoken, is now seldom heard. Bilingualism is fairly common, particularly among minorities who are conversant in Arabic. English is widely used in commerce.

Religion

Iraq is predominantly a Muslim country, in which the two major sects of Islam are represented more equally than in any other state. About three-fifths of the population is Shiʿi, and about two-fifths is Sunni. Largely for political reasons, the government has not maintained careful statistics on the relative proportion of the Sunni and Shiʿi populations. Shiʿis are almost exclusively Arab (with some Turkmen and Kurds), while Sunnis are divided mainly between Arabs and Kurds but include other, smaller groups, such as Azerbaijanis and Turkmen.

https://e.infogram.com/_/6eMneDoXty2FAIEVhfPW?parent_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.britannica.com%2Fplace%2FIraq%2FClimate&src=embed#async_embed

Sunnis

From the inception of the Iraqi state in 1920 until the fall of the government of Saddam Hussein in 2003, the ruling elites consisted mainly—although not exclusively—of minority Sunni Arabs. Most Sunni Arabs follow the Ḥanafī school of jurisprudence and most Kurds the Shāfiʿī school, although this distinction has lost the meaning that it had in earlier times.

The Shiʿah of Iraq

The Iraqi Shiʿah, like their coreligionists in Iran, follow the Twelver (Ithnā ʿAsharī) rite, and, despite the preeminence of Iran as a Shiʿi Islamic republic, Iraq has traditionally been the physical and spiritual centre of Shiʿism in the Islamic world. Shiʿism’s two most important holy cities, Najaf and Karbala, are located in southern Iraq, as is Kūfah, sanctified as the site of the assassination of ʿAlī, the fourth caliph, in the 7th century. Sāmarrāʾ, farther north, near Baghdad, is also of great cultural and religious significance to the Shiʿah as the site of the life and disappearance of the 12th, and eponymous, imam, Muḥammad al-Mahdī al-Ḥujjah. In premodern times southern and eastern Iraq formed a cultural and religious meeting place between the Arab and Persian Shiʿi worlds, and religious scholars moved freely between the two regions. Even until relatively recent times, large numbers of notable Iranian scholars could be found studying or teaching in the great madrasahs (religious schools) in Najaf and Karbala. The Iranian cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, for instance, spent many years lecturing at Najaf while in exile. Although Shiʿis constituted the majority of the population, Iraq’s Sunni rulers gave preferential treatment to influential Sunni tribal networks, and Sunnis dominated the military officer corps and civil service. Shiʿis remained politically and economically marginalized until the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime. Since the transition to elective government, Shiʿi factions have wielded significant political power.

Religious minorities

Followers of other religions include Christians and even smaller groups of Yazīdīs, Mandaeans, Jews, and Bahāʾīs. (See Mandaeanism; Bahāʾī faith.) The nearly extinct Jewish community traces its origins to the Babylonian Exile (586–516 bce). Jews formerly constituted a small but significant minority and were largely concentrated in or around Baghdad, but, with the rise of Zionism, anti-Jewish feelings became widespread. This tension eventually led to the massive Farhūd pogrom of June 1941. With the establishment of Israel in 1948, most Jews emigrated there or elsewhere. The Christian communities are chiefly descendants of the ancient population that was not converted to Islam in the 7th century. They are subdivided among various sects, including Nestorians (Assyrians), Chaldeans—who broke with the Nestorians in the 16th century and are now affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church—and members of the Syriac Orthodox and Eastern Orthodox churches. About one million Christians lived in Iraq when the Iraq War began. The population has since dwindled to below 250,000, mostly due to poverty and violence by Muslim extremists.

Settlement patterns

Iraq has a relatively low population density overall, but, in the fertile lowlands and the cities, densities are nearly four times the national average.

Rural settlement

The distribution of towns and villages in Iraq follows basic patterns established thousands of years ago. Although the proportion of urban dwellers has risen over time, about one-third of Iraqis still live in rural areas. Today several thousand villages and hamlets are scattered unevenly throughout the two-thirds of Iraq that is permanently settled. The greatest concentration of villages is in the valleys and lowlands around the Tigris and Euphrates. Most have between 100 and 2,000 houses, traditionally clustered tightly for defensive purposes. Their populations are engaged almost exclusively in agriculture, although essential services are located in the larger villages.

Villages in the foothills and mountains of the largely Kurdish northeast tend to be smaller and more isolated than those of lowland Iraq, which befits a lifestyle that is based on animal husbandry and only rarely on agriculture. The arid and semiarid areas in the west and south have sparse populations. The arid regions, along with the extensive Al-Jazīrah region northwest of Baghdad, were traditionally inhabited by nomadic Bedouin tribes, but few of these people remain in Iraq. Another lifestyle under threat is that of the Shiʿi marsh dwellers (Madan) of southern Iraq. They traditionally have lived in reed dwellings built on brushwood foundations or sandspits, but the damage done to the marshes in the 1990s has largely undermined their way of living. Rice, fish, and edible rushes have been staples, supplemented by products of the water buffalo.

Urban settlement

More than two-thirds of Iraq’s population are urban dwellers, and almost two-fifths of those are concentrated in the five largest cities: Baghdad, Basra, Mosul, Erbil, and Al-Sulaymāniyyah. There are also a considerable number of small towns, many of which are market centres, provincial capitals, or the headquarters of smaller local government districts. Attempts to stimulate the growth of selected small towns have had only modest success, and government efforts to stem the tide of people departing rural areas, through agricultural reform and other measures, have largely failed.

https://e.infogram.com/_/RinwZrCcCAkzai38fOOy?parent_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.britannica.com%2Fplace%2FIraq%2FArabs&src=embed#async_embed

Baghdad of Iraq

For a variety of reasons, rural migrants have been particularly drawn to Baghdad, the country’s political, economic, and communications hub. First, to minimize the danger of riots in the capital city, the Baʿath regime—in addition to a variety of security measures—made special efforts to maintain a minimal level of public services, even in the poorest neighbourhoods. This was especially important after the UN imposed an extended embargo on Iraqi trade in response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, making food rationing more necessary than ever before. Distributing rations was more efficient in the capital area. Second, chances for employment typically have been better in Baghdad than in other cities. This was true as early as the 1930s, when migrants began to move to the city. Since that time, Shiʿi Arabs from the south have been the largest migrant group in the city, a trend that was enhanced during the Iran-Iraq War as many refugees fled the southern war zones. Efforts to limit this influx, and even to reverse it, met with only limited success, and, by the beginning of the 21st century, Shiʿi Arabs represented a majority in the capital. The poor Shiʿi Arab Al-Thawrah (“Revolution”) quarter—known informally since 2003 as Sadr City after Muhammad Sadiq al-Sadr, a murdered Shiʿi cleric—alone houses more than a million people. Prior to the Iraq War, many Baghdad neighbourhoods contained a mix of Sunni and Shiʿi residents. These neighbourhoods became homogeneous as residents moved to safer areas amid the sectarian bloodshed that peaked about 2006. It is estimated that one-fifth of the country’s people live in the governorate of Baghdad, almost all of them in the city itself.

It is no coincidence that Baghdad’s celebrated predecessors, Babylon and the Sasanian capital, Ctesiphon, were located in the same general region. Baghdad, itself a city of legend, is located at the heart of what has long been a rich agricultural region, and the modern city is the undisputed commercial, manufacturing, and service capital of Iraq. Its growth, however, has necessitated costly projects, including elaborate flood-prevention schemes completed largely in the 1950s, the rehousing of hundreds of thousands of inhabitants of squalid shantytowns (ṣarīfahs) in the 1960s (and, on a much smaller scale, in 1979–80), and the construction of major domestic water and sewerage projects. The city was damaged during both the Persian Gulf War and the Iraq War and required major reconstruction of all parts of the infrastructure.

Regional centres

Basra, on the west bank of the Shaṭṭ al-ʿArab and formerly Iraq’s main port, is the centre of its southern petroleum sector and the hub of the country’s date cultivation. One of the great cities of Islamic history and heritage, it was badly damaged and largely depopulated during the Iran-Iraq War and, though partially reconstructed following that conflict, again suffered during the Persian Gulf War and subsequent fighting between Shiʿi rebels and government forces. Much of the city’s infrastructure (sewerage and potable water and health care facilities) remained in a state of disarray, with dire results for public health. Basra’s function as a port was taken over by Umm Qaṣr, a small deepwater port on the gulf.

Iraq’s third city, though now its second largest in terms of population, is Mosul, which is situated on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient Assyrian capital of Nineveh. Mosul is the centre for the upper Tigris basin, specializing in processing and marketing agricultural and animal products. It has grown rapidly, partly as a result of the influx of Kurdish refugees fleeing government repression in Iraqi Kurdistan. By the end of the 1990s, Mosul too had suffered from government neglect, and, relative to Baghdad, its infrastructure and health care facilities were in poor condition.

Demographic trends

The population of Iraq is young. About two-fifths of the population are under 15, while two-thirds are under 30. Its birth rate is high, and it has a low death rate due to its much smaller elderly population; less than one-seventh of Iraqis are over the age of 45. Women have a life expectancy of about 76 years, while men’s life expectancy is 73.

https://e.infogram.com/_/6ZvcoS67lEfK7ua6wddK?parent_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.britannica.com%2Fplace%2FIraq%2FThe-Shiah&src=embed#async_embed

Iraq has the fourth largest population in the Middle East, after Iran, Egypt, and Turkey. Yet demographic information since 1980 has been difficult to obtain and interpret, and outside observers often have been forced to use estimates. From 1990 a UN embargo on Iraq, which made travel to and from the country difficult, contributed considerably to the lack of information, but most important was the rule of more than 30 years by the Baʿathist regime, which was intent on controlling the flow of information about the country. The former Iraqi government sought to downplay unflattering demographic shifts in its Kurdish and Shiʿi communities while highlighting the effects of the UN embargo on health, nutrition, and overall mortality—particularly among the country’s children.

UN studies indicate that general levels of health and nutrition declined markedly after the introduction of the embargo in 1990 and before Iraq accepted the provisions of a UN program in late 1996 that allowed Iraq to sell a set quantity of oil in order to purchase food, medicine, and other human necessities. This situation led to substantial declines in the rates of birth, natural increase, and fertility and a noticeable increase in the death rate. Overall vital statistics in Iraq during the 1990s, however, remained above world averages and by the 21st century had begun to return to their prewar levels.

Because of Iraq’s relatively low population density, in the 20th century the government promoted a policy of population growth. The total fertility rate had declined since its peak in the late 1960s. This decline apparently resulted from the casualties of the two major wars—reaching possibly as many as a half million young and early-adult men—and subsequent difficulties related to the UN embargo, as well as an overall sense of insecurity among Iraqis. For the same reasons, it is reckoned that the rate of natural increase, though still high by world standards, had dropped markedly by the mid-1990s before it likewise rebounded.

The associated hardships of the early to mid-1990s and the first decade of the 21st century persuaded a number of Iraqis—at least those who were wealthy enough—to either leave the country or seek haven in the northern Kurdish region, where, thanks to international aid and a freer market, living conditions improved noticeably during the 1990s. Moreover, an estimated one to two million Iraqis—many of them unregistered refugees—fled the country to various destinations (including Iran, Syria, and Jordan) out of direct fear of government reprisal. During the Iraq War, more than 1.6 million Iraqis fled the country, and more than 1.2 million were displaced internally.

Beyond the out-migration of a significant number of Iraqis, the major demographic trends in the country since the 1970s have been forced relocation—particularly of the Iranian population and, more recently, of the Kurds—forced ethnic homogenization, and urbanization. Eastern Iraq has traditionally formed part of a transition zone between the Arab and Persian worlds, and, until the Baʿath regime came to power in 1968, a significant number of ethnic Persians lived in the country (in the same way large numbers of ethnic Arabs reside in Iran). Between 1969 and 1980, however, they—and many Arabs whom the regime defined as Persian—were deported to Iran.

Kurds have traditionally populated the northeast, and Sunni Arabs have traditionally predominated in central Iraq. During the 1980s the Baʿath regime forcibly moved tens of thousands of Kurds from regions along the Iranian border, with many Kurds dying in the process, and subsequently relocated large numbers of Arabs to areas traditionally inhabited by Kurds, particularly in and around the city of Kirkūk. Kurds in those regions have, likewise, been expelled, and many of Iraq’s estimated half million internally displaced persons prior to the Iraq War were Kurds. Further, the regime systematically compelled large numbers of Kurds and members of smaller ethnic groups to change their ethnic identity, forcing them to declare themselves Arabs. Those not acquiescing to this pressure faced expulsion, physical abuse, and imprisonment.

Iraqis have been slowly migrating to urban areas since the 1930s. Population mobility and urban growth have, to some extent, created a religious and cultural mix in several large cities, particularly in Baghdad. (There has been little change in the overall ethnic patterns of the country, however, except through instances of forced migration.) Many Kurds have moved either to larger towns in Kurdistan or to larger cities such as Mosul or Baghdad. Few Kurds have moved willingly to the south, where Arab Shiʿis have traditionally predominated. The latter have moved in substantial numbers to larger towns in the south or, particularly during the fighting in the 1980s, to largely Shiʿi neighbourhoods in Baghdad. Sunnis migrating from rural areas have moved mostly to areas of Baghdad with majorities of their ethnic and religious affinities.

From the mid-1970s until 1990, labour shortages drew large numbers of foreign workers, particularly Egyptians, to Iraq; at its height the number of Egyptians may have exceeded two million. Virtually all foreign workers left the country prior to the Persian Gulf War, and few, if any, have returned.

Economy of Iraq

Overview

Iraq’s economy was based almost exclusively on agriculture until the 1950s, but after the 1958 revolution economic development was considerable. By 1980 Iraq had the second largest economy in the Arab world, after Saudi Arabia, and the third largest in the Middle East and had developed a complex, centrally planned economy dominated by the state. Although the economy, particularly petroleum exports, suffered during the Iran-Iraq War—gross domestic product (GDP) actually fell in some years—the invasion of Kuwait, Iraq’s subsequent defeat in the Persian Gulf War, and the UN embargo beginning in 1990 dealt a far greater blow to the financial system. Little hard evidence is available on Iraq’s economy after 1990, but the best estimates available indicate that, in the year following the Persian Gulf War, GDP dropped to less than one-fourth of its previous level. Under the UN embargo the Iraqi economy languished for the next five years, and it was not until the Iraqi government implemented the UN’s oil-for-food program in 1997 that Iraq’s GDP again began to experience positive annual growth.

Following the initial phase (2003) of the Iraq War, the oil-for-food program was ended, sanctions were lifted, and the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), made up of civil administrators appointed by the United States, took over Iraq’s public sector. International donors pledged billions of dollars in aid for Iraq’s reconstruction at a donor conference in Madrid in October 2003. Iraq’s huge foreign debt, largely accumulated through heavy war expenditures under Saddam Hussein, was reduced in 2004 when the Paris Club, a group of 19 wealthy creditor nations, agreed to cancel 80 percent of Iraq’s $40 billion debt to 19 members.

Oil production and economic development both declined after the start of the Iraq War, and the economy faced serious problems, including the negative impact of continuing violence; a high rate of inflation; an oil sector hampered by a shortage of replacement parts, antiquated production methods, and outdated technology; a high rate of unemployment; a seriously deteriorated infrastructure; and a private sector inexperienced in modern market practices. The CPA was largely unprepared to cope with these challenges, and its handling of the Iraqi economy was marred by mismanagement, poor planning, and waste. American administrators’ efforts to quickly implement liberal reforms did little to improve conditions for Iraqis or calm a growing insurgency against U.S. forces.

Under the Iraqi administrations that governed after the dissolution of the CPA in June 2004, reconstruction proceeded unevenly. Relatively secure areas such as the Kurdish region saw quick progress, while most of the country continued to suffer from high unemployment, soaring prices for basic goods, and inadequate access to services. Modest signs of improvement began to appear in 2007 as violence began to decrease. Inflation returned to manageable levels in that year, and in 2009 oil export revenues returned to prewar levels. However, crumbling infrastructure, violence, and corruption continued to weigh down Iraq’s recovery.

Economic development

Oil revenues almost quadrupled between 1973 and 1975, and, until the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War, this enabled the Baʿath regime to set ambitious development goals, including building industry, reducing the quantity of imported manufactured goods, expanding agriculture (though Iraq has not attained self-sufficiency), and increasing significantly its non-oil exports. Investment in infrastructure was high, notably for projects involving irrigation and water supply, roads and railways, and rural electrification. Health services were also greatly improved. War with Iran in the 1980s, however, delayed many projects and heavily damaged the country’s physical infrastructure, especially in the southeast, where most of the fighting occurred. There was little reprieve after the war was over, as the Persian Gulf War further devastated Iraq’s infrastructure and undid many of the advances of earlier decades. Attacks by the U.S.-led coalition did extensive damage to the communication and energy systems. When electricity failed, other systems were seriously affected, and a lack of spare parts led to further deterioration. In many parts of the country, these conditions persisted into the 21st century and were worsened by the Iraq War.

State control

Under the socialist Baʿath Party, the economy was dominated by the state, with strict bureaucratic controls and centralized planning. Between 1987 and 1990 the economy liberalized somewhat in an attempt to encourage private investment, particularly in small industrial and commercial enterprises, and to privatize unprofitable public assets. Entrepreneurs were encouraged to draw on funds that they had managed to transfer abroad, without threat of government reprisal or interference, and the government was able to divest itself of a number of enterprises. Yet, generally speaking, the privatization policy did not do well, mainly because elements within the bureaucracy and the security service—fearing that this course of action imperiled their interests and obviated socialist policy—objected to it but also because potential investors feared that the government might arbitrarily reverse the plan. In addition, many of the public assets offered for sale were unprofitable. After Iraq invaded Kuwait, the privatization policy died out, though private enterprise continued in the form of small- and medium-sized businesses and light industries.

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing

About one-eighth of Iraq’s total area is arable, and another one-tenth is permanent pasture. A large proportion of the arable land is in the north and northeast, where rain-fed irrigation dominates and is sufficient to cultivate winter crops, mainly wheat and barley. The remainder is in the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, where irrigation—approximately half of Iraq’s arable land is irrigated—is necessary throughout the year. The cultivated area declined by about half during the 1970s, mainly because of increased soil salinity, but grew in the 1980s as a number of large reclamation projects, particularly in the central and northwestern areas, were completed. In addition, droughts in Turkey frequently reduced the amount of Euphrates water available for irrigation in the south. Although the Tigris is affected less by drought—because it has a wider drainage area, including tributaries in Iran—it has been necessary to construct several large dams throughout the river system to store water for irrigation. Careful management of the soils has been necessary to combat salinity. Increases in water usage in the upstream states, Turkey and Syria, and the poor condition of Iraq’s water infrastructure have contributed to recurring severe water shortages, forcing farmers to abandon farmland.

Agriculture, which has traditionally accounted for one-fourth to one-third of Iraq’s GDP, now accounts for about 10 percent. The country’s agricultural sector faces many problems in addition to soil salinity and drought, including floods and siltation, which impede the efficient working of the irrigation system. A lack of access to fertilizer and agricultural spare parts after 1990 and a lengthy drought in the early 21st century led to a decrease in agricultural production.

Before the revolution of 1958, most of the agricultural land was concentrated in the hands of a few powerful landowners. The revolutionary government began a program of land reform, breaking up the large estates and distributing the land to peasant families and limiting the size of private holdings. The Baʿathist government that took over in 1968 originally encouraged public ownership and established agricultural cooperatives and collective farms, but those proved to be inefficient. After 1983 the government rented state-owned land to private concerns, with no limit on the size of holdings, and from 1987 it sold or leased all state farms. Membership in a cooperative and the use of government marketing organizations ceased to be obligatory.

The chief crops are barley, wheat, rice, vegetables, corn (maize), millet, sugarcane, sugar beets, oil seeds, fruit, fodder, tobacco, and cotton. Yields vary considerably from year to year, especially in areas of rain-fed cultivation. Date production—Iraq was once the world’s largest date producer—was seriously damaged during the Iran-Iraq War and approached prewar levels only in the early 21st century. Animal husbandry is widely practiced, particularly among the Kurds of the northeast, and livestock products, notably milk, meat, hides, and wool, are important.

Timber resources are scarce and rather inaccessible, being situated almost entirely in the highlands and mountains of the northeast in Iraqi Kurdistan. The resources that are readily available are used almost exclusively for firewood and the production of charcoal. Limited amounts of timber are used for local industry, but most wood for industrial production (for furniture, construction, and other purposes) must be imported. Afforestation projects to supply new forest area and reduce erosion have met with limited success.

Iraq harvests both freshwater and marine fish for local consumption and also supports a modest aquaculture industry. The main freshwater fish are various species of the genus Barbus and carp, which are pulled from Iraqi national waters and from the Persian Gulf by Iraq’s small domestic fleet. Inland bodies provide by far the largest source of fish. Various types of shad, mullet, and catfish are fished in the lakes, rivers, and streams, and fish farms mostly provide varieties of carp. There is no industrial fish-processing sector, and most fish is consumed fresh by the domestic market. Fishing contributes only a tiny fraction to GDP.

Resources and power

Petroleum and natural gas

Petroleum is Iraq’s most valuable mineral—the country has some of the world’s largest known reserves and, before the Iran-Iraq War, was the second largest oil-exporting state. Oil production contributes the largest single portion to GDP and constitutes almost all of Iraq’s foreign exchange. Iraq is a founding member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), but disagreements over production quotas and world oil prices have often led Iraq into conflict with other members.

Oil was first discovered in Iraq in 1927 near Kirkūk by the foreign-owned Turkish Petroleum Company, which was renamed the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC) in 1929. Finds at Mosul and Basra followed, and several new fields were discovered and put into production in the 1940s and ’50s. New fields have continued to be discovered and developed.

The IPC was nationalized in 1972, as were all foreign-owned oil companies by 1975, and all facets of Iraq’s oil industry were thereafter controlled by the government through the Iraq National Oil Company and its subsidiaries. During the war with Iran, production and distribution facilities were badly damaged, and after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait—which was itself partly prompted by disagreements over production quotas and disputes over oil field rights—the UN embargo on Iraq halted all exports. Under the embargo Iraq exported little or no oil until the oil-for-food program was implemented. By the early 21st century, oil production and exports had risen to roughly three-fourths of the levels achieved prior to the Persian Gulf War. Oil production rebounded slowly following the initial phase of the Iraq War.

Oil pipelines

Because Iraq has such a short coastline, it has depended heavily on transnational pipelines to export its oil. This need has been compounded by the fact that Iraq’s narrow coastline is adjacent to that of Iran, a country with which Iraq frequently has had strained relations. Originally (1937–48) oil from the northern fields (mainly Kirkūk) was pumped to the Mediterranean Sea through Haifa, Palestine (now in Israel), a practice that the Iraqis abandoned with the establishment of the Jewish state. Soon thereafter pipelines to the Mediterranean were built to Bāniyās, Syria, and through Syria to Tripoli, Lebanon. In 1977 a large pipeline was completed to the Turkish Mediterranean coast at Ceyhan. When the first Turkish line was completed, Iraq ceased using the Syrian pipelines and relied on the outlet through Turkey and on new terminals on the Persian Gulf (although export through Syria briefly resumed in the early 1980s). By 1979 Iraq had three gulf terminals—Mīnāʾ al-Bakr, Khawr al-Amaya, and Khawr al-Zubayr—all of which were damaged during one or the other of Iraq’s recent wars. In 1985 Iraq constructed a new pipeline that fed into the Petroline (in Saudi Arabia), which terminated at the Red Sea port of Yanbuʿ. In 1988 that line was replaced with a new one, but it never reached full capacity and was shut down, along with all other Iraqi oil outlets, following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait.

In December 1996 the Turkish pipeline was reopened under the oil-for-food program. Later the gulf terminal of Mīnāʾ al-Bakr also was revived, and in 1998 repairs were begun on the Syrian pipeline. Following the start of the Iraq War in 2003, Iraq’s pipelines were subjected to numerous acts of sabotage by guerrilla forces.

Other minerals and energy

Exploitation of other minerals has lagged far behind that of oil and natural gas. It seems likely that Iraq has a good range of these untapped resources. Huge rock sulfur reserves—estimated to be among the largest in the world—are exploited at Mishraq, near Mosul, and in the early 1980s phosphate production began at ʿAkāshāt, near the Syrian border; the phosphates are used in a large fertilizer plant at Al-Qāʾim. Lesser quantities of salt and steel are produced, and construction materials, including stone and gypsum (from which cement is produced), are plentiful.

Iraq’s electrical production fails to meet its needs. Energy rationing is pervasive, and mandatory power outages are practiced throughout the country. This is largely because of damage by the Persian Gulf War, which destroyed the bulk of the country’s power grid, including more than four-fifths of its power stations and a large part of its distribution facilities. Despite a shortage of spare parts, Iraq was able—largely through cannibalizing equipment—to reconstruct roughly three-fourths of its national grid by 1992. By the end of the decade, however, this level of energy production had decreased, in part as a result of a reduced level of hydroelectric generation caused by drought but also because there continued to be a lack of replacements for aging components. Damage from the Iraq War has been less severe, but energy production remains below installed capacity.

The bulk of electricity generation is by thermal plants. Even in the best of times—despite the many dams on Iraq’s rivers—the hydroelectricity produced is below installed capacity. The largest hydroelectric plants are at the Mosul Dam on the Tigris, the Dokan Dam on the Little Zab River, the Darbandikhan Dam on the Diyālā in eastern Kurdistan, and the Sāmarrāʾ Dam on Lake Al-Tharthār. A Chinese company completed a new plant near Kirkūk in 2000.

Manufacturing

The manufacturing sector developed rapidly after the mid-1970s, when government policy shifted toward heavy industrialization and import substitution. Iraq’s program received assistance from many countries, particularly from the former Soviet Union. The state generally has controlled all heavy manufacturing, the oil sector, power production, and the infrastructure, although private investment in manufacturing was at times encouraged. Until 1980 most heavy manufacturing was greatly subsidized and made little economic sense, but it brought prestige for the Baʿath regime and later, during the Iran-Iraq War, served as a basis for the country’s massive military buildup. Petrochemical and iron and steel plants were built at Khawr al-Zubayr, and petrochemical production and oil refining were greatly expanded both at Basra and at Al-Musayyib, 40 miles (65 km) south of Baghdad, which was designated as the site of an enormous integrated industrial complex. In addition, a wide range of industrial activities were started up, some of which were boosted by the Iran-Iraq War, notably aluminum smelting and the production of tractors, electrical goods, telephone cables, and tires. Petrochemical products for export also were expanded and diversified to include liquefied natural gas, bitumen, detergents, and a range of fertilizers.

The combined results of the Iran-Iraq War, both the Persian Gulf War and the Iraq War, and, most of all, the UN embargo eroded Iraq’s manufacturing capacity. Within its first two years, the embargo had cut manufacturing—which was already well below its highs of the early 1980s—by more than half. After 1997, however, there was an increase in manufacturing output, in both the public and the private sectors, as replacement parts and government credit became available. By the end of the decade, large numbers of products long unavailable to consumers were once again on the market, and almost all the factories that were operating before the imposition of the embargo had resumed production, albeit at somewhat lower levels.

Finance

All banks and insurance companies were nationalized in 1964. The Central Bank of Iraq (founded in 1947 and one of the first central banks in the Arab world) has the sole right to issue the dinar, the national currency. The Rafidain Bank (1941) is the oldest commercial bank, but in 1988 the state founded a second commercial bank, the Rashid (Rasheed) Bank. There are also three state-owned specialized banks: the Agricultural Co-operative Bank (1936), the Industrial Bank (1940), and the Real Estate Bank (1949). Beginning in 1991 the government authorized private banks to operate, although only under the strict supervision of the central bank. The Baghdad Stock Exchange opened in 1992.

By 2004, after three major wars and years of international isolation, the national accounts were in disarray, and the country was saddled with an enormous national debt. At the end of the Persian Gulf War, the value of the formerly sound dinar plummeted in the face of rampant inflation. The UN embargo made it difficult for Iraqi banks to operate outside the country, and, under UN auspices, numerous Iraqi assets and accounts, including those in Iraq’s financial institutions, were frozen and later seized by host governments in order to pay the country’s numerous outstanding debts. Under the stipulations of the oil-for-food program, all revenues derived from the export of Iraqi oil were placed in escrow and supervised by the international community. After the initial phase of the Iraq War, portions of Iraq’s external debt were canceled by creditor nations beginning in 2004. By mid-2007, inflation had returned to safe levels.

Trade of Iraq

Before the UN embargo, Iraq was a heavy importer. The chief imports included military ordnance, vehicles, industrial and electrical goods, textiles and clothing, and construction materials. About one-fourth of import spending was on foodstuffs. Exports—though dominated by oil, which accounted for nearly all of total export value—were relatively diverse and included such items as dates, cotton, wool, animal products, and fertilizers. All legal international trade ground to a virtual halt following the invasion of Kuwait and the imposition of the embargo. Only with the start of the oil-for-food program did Iraq again begin to engage in international trade—albeit under strict UN supervision. Beginning in 2002 the UN eased trade restrictions to allow a broader range of imports, and the following year the embargo was lifted. Foodstuffs are still imported in large quantities, as are consumer goods of all types. Exports now consist mostly of petroleum and petroleum products, which are shipped to a number of countries, primarily to countries in Asia but also to countries in the European Union and the Americas. Imports come largely from Asia and other Arab countries.

https://e.infogram.com/_/Qqlp2lOLI3RcQKSYlxJr?parent_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.britannica.com%2Fplace%2FIraq%2FOil-pipelines&src=embed#async_embed

https://e.infogram.com/_/Z97zDOqzRF2wjYDZVulW?parent_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.britannica.com%2Fplace%2FIraq%2FOil-pipelines&src=embed#async_embed

Services

Like every other part of the economy, the service sector suffered during the embargo. Retail sales fell off as unemployment rose and as the buying power of the dinar sharply decreased. A large portion of every Iraqi’s salary—even among the once-thriving middle class—went to such necessities as food and shelter. Iraq’s somewhat isolated geographic location and its decades of near perpetual political instability have seriously impeded the possibility that tourism, in spite of the country’s deep historical wealth, might soon become a major source of national income. The only sector of the service economy that consistently thrived throughout the embargo was the construction industry. The government invested a large portion of its limited resources in repairing the damage of the Persian Gulf War (particularly in and around Baghdad) and to constructing grandiose monuments and palaces for the regime and its leader, Saddam Hussein.

Labour and taxation

Labour laws enacted following the revolution offer protection to employees, including minimum wages and unemployment benefits; traditionally there have also been benefits for maternity, old age, and illness. It is unclear how these measures have been honoured since the early 1990s. Trade unions were legalized in 1936, but their effectiveness was limited by government and Baʿath Party control. Iraq’s only authorized labour organization is the General Federation of Trade Unions (GFTU), established in 1987, which is affiliated with the International Confederation of Arab Trade Unions and the World Federation of Trade Unions. Under the Baʿath government, workers in the private sector were allowed to join only local unions associated with the GFTU, which in reality was closely tied to, and controlled by, the party and was largely a vehicle for Baʿathist ideology. Collective bargaining traditionally has not been practiced, and workers effectively have been barred from striking. Under labour laws adopted in that period, children under 14 years of age are allowed to work only in small family businesses, and those under 18 may work only a limited number of hours. In reality, however, the extreme economic situation that began in the 1990s forced many children to enter the workforce. Unemployment and underemployment have been extremely high since the 1990s—a considerable change for a country that had traditionally imported labour. As in many Islamic countries, the standard workweek is Sunday through Thursday, but many labourers toil six or seven days per week, some at more than one job.

Since the oil boom of the 1970s, the overwhelming majority of government revenue has been generated by the export and sale of petroleum. As a consequence, Iraq’s system of taxation is only poorly developed. The government scrambled to find new sources of revenue after the UN embargo was imposed in 1990, but these were few and consisted largely of sporadic taxation, property confiscation (mainly from enemies of the regime), and the government monopoly over export trade—largely clandestine shipments of oil—in defiance of the embargo. After the oil-for-food program was established, oil revenues were held in escrow by the UN. Following the start of the Iraq War, the country relied on international aid to augment income from oil exports.

Transportation and telecommunications

Iraq’s transport system encompasses all kinds of travel, both ancient and contemporary. In some desert and mountain regions, the inhabitants still rely on camels, horses, and donkeys. Despite the disruption caused by events since 1980, the country’s transportation systems are, by the standards of the region, reasonably high.

The road network has been markedly improved since the 1950s, and more than four-fifths of the road mileage is paved. There are good road links with neighbouring countries, particularly with Kuwait and Jordan. The most extensive road network is in central and southern Iraq.

The rail system is controlled by Iraqi Republic Railways. The main lines include a metre-gauge line from Baghdad to Kirkūk and Erbil and a standard-gauge line from Baghdad to Mosul and Turkey. To the south a standard-gauge line from Baghdad reaches Basra and Umm Qaṣr. A line links Iraq with the Syrian railway system. International rail service was interrupted during the political turmoil of the 1980s and was not reestablished with Syria until 2000 or with Turkey until 2001. The rail lines were damaged by looting during the Iraq War and required significant repairs.

Rivers, lakes, and channels have long been used for local transport. For large vessels, river navigation is difficult because of flooding, shifting canals, and shallows. Nevertheless, the Tigris is navigable by steamers to Baghdad, and smaller craft can travel upstream to Mosul. Navigation of the Euphrates is confined to small craft and large rafts that carry goods downstream. Oceangoing ships can reach Basra, 85 miles (135 km) upstream on the Shaṭṭ al-ʿArab, only through regular dredging. Until the Iran-Iraq War, Basra handled the great bulk of Iraq’s trade, but since then—and even more so since 1996—Umm Qaṣr has been developed as an alternative port. It is linked with Al-Zubayr, 30 miles (50 km) inland, via the canalized Khawr al-Zubayr. Much Iraqi trade also passes through the Jordanian port of Al-ʿAqabah, from which goods are carried overland by truck. Since 1999 merchandise also has come through Syria’s port city of Latakia.

The national airline, Iraqi Airways, was founded in 1945, and domestic air traffic was relatively light at the outbreak of the Persian Gulf War. A ban on flights south of latitude 32° N (since 1996, 33° N) and north of 36° N (the so-called “no-fly zones”) that was established after the war forced domestic air traffic virtually to cease until late 2000. There are international airports at Baghdad (the country’s main point of entry) and Basra, as well as four regional airports and several large military fields.

Iraq’s telecommunication network, once one of the best in the region, was heavily damaged during the Persian Gulf War and was further degraded in 2003. The network has been repaired only partially and has suffered from inadequate maintenance and a chronic lack of spare parts. Services that are available are of a poor quality. There are approximately three main telephone lines per hundred residents and only slightly greater access to television, with less than one set per 10 residents. About one-fifth of the population has regular access to radio. All television and radio broadcast stations were either directly or indirectly controlled by the government, but after 2003 restrictions were dropped, and television service via satellite boomed. Cellular telephone service, unavailable under the Baʿath government, is now accessible in urban areas, and Internet access is available to a much wider audience.

Government and society

Constitutional framework

From 1968 to 2003 Iraq was ruled by the Baʿath (Arabic: “Renaissance”) Party. Under a provisional constitution adopted by the party in 1970, Iraq was confirmed as a republic, with legislative power theoretically vested in an elected legislature but also in the party-run Revolutionary Command Council (RCC), without whose approval no law could be promulgated. Executive power rested with the president, who also served as the chairman of the RCC, supervised the cabinet ministers, and ostensibly reported to the RCC. Judicial power was also, in theory, vested in an independent judiciary. The political system, however, operated with little reference to constitutional provisions, and from 1979 to 2003 Pres. Saddam Hussein wielded virtually unlimited power.

Following the overthrow of the Baʿath government in 2003, the United States and its coalition allies established the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), headed by a senior American diplomat. In July the CPA appointed the 25-member Iraqi Governing Council (IGC), which assumed limited governing functions. The IGC approved an interim constitution in March 2004, and a permanent constitution was approved by a national plebiscite in October 2005. This document established Iraq as a federal state in which limited authority—over matters such as defense, foreign affairs, and customs regulations—was vested in the national government. A variety of issues (e.g., general planning, education, and health care) are shared competencies, and other issues are treated at the discretion of the district and regional constituencies.

The constitution is in many ways the framework for a fairly typical parliamentary democracy. The president is the head of state, the prime minister is the head of government, and the constitution provides for two deliberative bodies, the Council of Representatives (Majlis al-Nawwāb) and the Council of Union (Majlis al-Ittiḥād). The judiciary is free and independent of the executive and the legislature.

The president, who is nominated by the Council of Representatives and who is limited to two four-year terms, holds what is largely a ceremonial position. The head of state presides over state ceremonies, receives ambassadors, endorses treaties and laws, and awards medals and honours. The president also calls upon the leading party in legislative elections to form a government (the executive), which consists of the prime minister and the cabinet and which, in turn, must seek the approval of the Council of Representatives to assume power. The executive is responsible for setting policy and for the day-to-day running of the government. The executive also may propose legislation to the Council of Representatives.

The Council of Representatives does not have a set number of seats but is based on a formula of one representative for every 100,000 citizens. Ministers serve four-year terms and sit in session for eight months per year. The council’s functions include enacting federal laws, monitoring the performance of the prime minister and the president, ratifying foreign treaties, and approving appointments; in addition, it has the authority to declare war.